Rainforest Destruction, One of Humanity's Deepest Spiritual Crises of Modern Times

By Irina Bright.

This article is part of our Environment section

See the complete list of all our Articles about Rainforests here.

Indeed, tropical forest is a victim of a spiritual crisis in humanity. The destruction of tropical forest reflects an all too-widespread willingness to submit to an economic determinism every bit as rigid as that of Marx.

~ Egbert Giles Leigh Jr. (Ref. 1)

Rainforest Destruction, Madagascar

Rainforest Destruction, Madagascar© Jonathan Talbot

World Resources Institute, 2003

We learn from Columbia Encyclopedia that in very early times forests covered virtually the whole land surface of the Earth, apart from the areas of perpetual snow (such as the north pole). (Ref. 2)

And as recently as 19 th century, tropical rainforests in their own right covered around 20% of all the dry land area of the Earth, but this figure was only 7% by the end of the 20 th century. (Ref. 3)

Probably the main fundamental factor that has been invariably pushing rainforest destruction more and more over the decades and indeed centuries, is the demand for the rainforest as a enormous economic and social resource.

First of all, tropical rainforests are “treasure troves of nature” – they contain endless supplies of resources widely used in human societies, such as food, timber, raw materials etc.

Second, rainforests cover huge swathes of land. And the land has always been a limited resource required for accommodation of ever growing human populations.

Some Historical Aspects of Rainforest Destruction

It’s interesting to note that deforestation as such started taking place some half a million years ago – when people first started using fire. (Ref. 4)

You’ll be surprised to learn that as much as nine-tenths of all deforestation (including all the forests, not only tropical rainforests) may have occurred before 1950. (Ref. 5)

During the Middle Ages, Europe witnessed an accelerated rate of rainforest destruction due to a significant increase in the population numbers and, as a result, increased levels of economic activity. (Ref. 6)

Michael Williams of History Today notes that:

During the 450 years from 1492 to c. 1950 Europe burst out of the confines of the continent with far-reaching consequences for the forests of the rest of the world. Its capitalistic economy commoditised nearly all it found, creating wealth out of nature, be it land, trees, animals, plants or people. Enormous strains were put on the global forest resource by a steadily increasing population (just over 400 million in 1500 to nearly 2.5 billion in 1950), also by rising demands for raw materials and food with urbanisation and industrialisation, first in Europe and, after the mid-nineteenth century, in the United States. (Ref. 7)

He goes on to mention:

Deforestation in Brazil

Deforestation in Brazil

In the sub-tropical and tropical forests, European systems of exploitation led to the harvesting of indigenous tree crops (e.g., rubber, hardwoods), and, in time, to the systematic replacement of the original forest by `plantation' crops grown for maximum returns in relation to the capital and labour (usually slave or indentured) inputs.

Classic examples of this were the highly profitable crops of sugar in the West Indies; coffee and sugar in the sub tropical coastal forests of Brazil; cotton and tobacco in the southern United States; tea in Sri Lanka and India; and, later, rubber in Malaysia and Indonesia.

In eastern Brazil, over half of the original 780,000 sq km of the huge subtropical forest that ran down the eastern portions of the country had disappeared by 1950 through agricultural exploitation and mining. In Sao Paulo state alone the original 204,500 sq km of forest was reduced to 45,500 sq km by 1952. (Ref. 8)

and:

During these centuries deforestation was also well under way in Europe itself, which was being colonised internally. This was particularly true in the mixed-forest zone of central European Russia, where over 67,000 sq km were cleared between the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. (Ref. 9)

So, rainforest destruction is not a new phenomenon.

But …

It’s not just the use of rainforests for consumption as such, but the sheer speed of rainforest destruction from 1950 onwards that has brought home the real plight of these ancient ecosystems to the rest of humanity.

Current Status of Rainforest Destruction

Below I quote some statistics on the most recent rates of rainforest destruction as taken from the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. (Ref. 10)

Let’s analyse some specific tropical regions that are host to the most significant areas of rainforest.

So:

1) South America (including Brazil), home to the world’s largest rainforest, the Amazon, was losing annually around 0.44% of its total rainforest area for the period of 1990 – 2000, and around 0.50% of its total rainforest area for the period of 2000 – 2005.

This statistics highlights the fact that the annual rates of rainforest destruction in this region actually increased at the beginning of the 21 st century, as compared to the last decade of the 20 th century.

Some authors have mentioned that if this rate of deforestation continues as it is, we will see only 60% of the Amazon’s total area left by 2050. (Ref. 11)

Not something to be cheery about …

2) South and South-East Asia (including Indonesia) probably sustained the highest rates of rainforest loss. This region was losing annually around 0.8% of its total tropical forest area for the period of 1990 – 2000, and around 1% for the period of 2000 – 2005.

The same here. This region witnessed increased annual rates of deforestation at the beginning of this century as compared to the end of the last one.

3) Western and Central Africa (including Democratic Republic of the Congo) was losing annually around 0.6% of its total tropical forest area for the period of 1990 – 2000, and around 0.5% for the period of 2000 – 2005.

4) There were signs of improvement in Central America (with countries such as Costa Rica and Panama), whose annual rates of rainforest loss went down from 1.5% of the region’s total forest area for the period of 1990 – 2000 to 1.2% for the period of 2000 – 2005.

5) The Caribbean was another region with improved forest statistics. It was already gaining more forest area at the average annual rate of 0.6% of its total forest area for the period of 1990 – 2000. And this figure was even better for the period of 2000 – 2005: 0.9%.

Among predominantly negative statistics on rainforest loss, there is some positive news as well.

For example, as we’ve already mentioned in the Tropical Rainforests article, the rate of the Amazon rainforest’s destruction was lowest since 1991. (Ref. 12)

Another good example is Costa Rica. Whereas this country was losing annually around 0.8% of its total forest area for the period of 1990 – 2000, between 2000 and 2005 it started gaining more forest areas by around 0.1% annually.

So what are the main driving forces of tropical deforestation?

Let’s re-emphasise this important statement once again: The demand for rainforest resources is driven by economic forces both in developed and developing countries.

There’s no doubt about it, developed countries lay huge claims on the rainforest resources, by extracting such highly popular items as coffee and bananas, timber, medicines etc.

I really like this quote by Elizabeth Mygatt:

Industrial countries may be leading the way in conserving their own forests, but their demand for wood drives much of the deforestation elsewhere on the globe. (Ref. 13)

Also, there is no doubt about the fact that rainforest resources are widely used for local economies, that is by developing countries themselves.

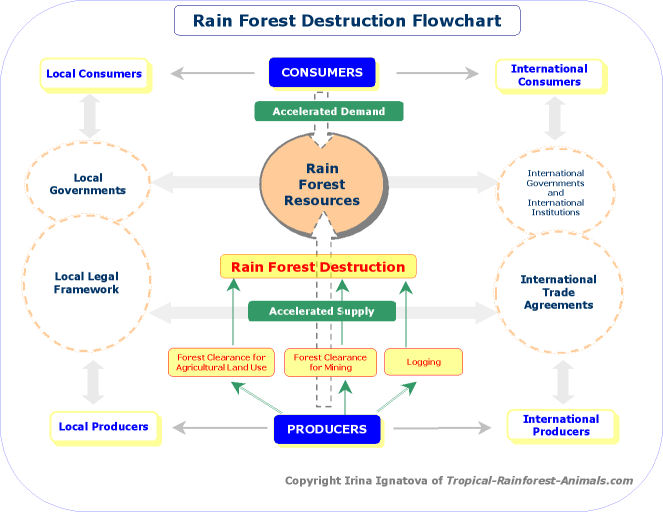

Have a look at this simplified Rainforest Destruction Flowchart below.

The chart puts a special focus on Accelerated Demand and Accelerated Supply.

These are the main fundamental drivers of the rainforest destruction of most recent times.

And who are the main agents of rainforest destruction?

Now let’s see who actually “executes” rainforest destruction.

But before that it would useful to analyse the main economic activities for which rainforests are cleared.

The chart above highlights several major activities for the sake of which the forests are cleared.

1. Forest Clearance for Agricultural Land Use.

Land indeed has been historically in high demand, and especially so during the times of population explosions.

So, rainforest land is used for:

These are the plantations set up to grow crops for export which bring in valuable foreign currency to an exporting country. Some of most popular crops are bananas, coffee, sugar cane.

- Cattle ranching.

This type of activity is very popular in Latin America. (Ref. 14) Cattle are another example of a “cash” product. Rainforests are cleared to gain land for cattle ranching. Meat is then exported to foreign markets to earn more income. See how rancher shooting directly affects the survival of one of the most charismatic rainforest animals – the jaguar.

- Subsistence farming.

The main purpose of this type of activity is for farmers to provide just enough food for themselves and their families. Normally this activity does not generate any income from the food sales.

“Agents of destruction” here?

Mostly local farmers and ranchers clearing the rainforests, quite often by applying a “slash-and-burn” method. But sometimes also some major international corporations (Ref. 15) which have their own agendas for investing in these enterprises.

Quite a recent phenomenon is the production of biofuels which are becoming very popular (though controversial) for use in transport and some other areas. One of the most popular biofuels, for example, is ethanol fuel. It can be produced from sugar cane. Large areas of land are required to grow sugar cane. What may quite often happen is that rainforest is cleared to gain more land for growing sugar cane, and thus causing rainforest destruction.

2. Forest Clearance for Mining and Natural Resource Development.

Mining for underground resources (such as gold, precious metals) as well as production of natural resources such as oil and gas contained within rainforests offers such significant incomes for a host country that it is too strong a temptation to resist. Especially that many developing countries have to use this sort of revenue to service their foreign debts.

It is another major cause of rainforest destruction.

For an excellent example of this, see how the oil production in the Ecuador rainforest brought on one of the worst cases of toxic pollution ever.

“Agents of destruction” here?

Natural resource companies (a lot of them international).

3. Forest Clearance by Logging.

This is probably one of the most (in)famous causes of rainforest destruction all over the world.

This sort of activity offers high short-term returns with no long-term investment commitment for a logging company.

Generally, it is difficult to regulate logging as such, and especially to protect rainforests from illegal logging activities (which has been estimated at around 10% of the total global timber trade (Ref. 16)).

“Agents of destruction” here?

Logging companies (surprise – surprise), as well as illegal loggers of course.

4. Other activities that cause rainforest destruction.

- Construction of developmental projects such as roads and dams.

See a discussion of the potential effects of Plan Puebla Panama ("a development corridor" between the south of Mexico and Panama) on Panama rainforest. Also, find out how the construction of dams during the Panama Canal construction, completed by 1914, caused one of the most serious rainforest destructions ever.

- Use of forest wood for fuel.

- Population resettlement programmes.

Special Note on Rainforest Pollution

Damage is inflicted on tropical rainforests not only through their direct physical destruction by the activities described above.

It is also caused by certain types of on-going environmental pollution (rather than one-off events of structural destruction of rainforest ecosystems). Such on-going pollution is widely present in the environment that the rainforests rely upon, for example, in the air sphere.

The rainforests act as pollution sinks - it means they "soak up" the environmental pollution that is present in the air that the forests breathe in. If the levels of such air pollution significantly exceed the levels that the forests can safely deal with, such situation leads to rainforest degradation (rather than outright forest destruction).

Additionally, deforestation (as a result of rainforest destruction) is a cause of global warming pollution and presents a major challenge as a huge source of carbon dioxide emissions.

For more details on how environmental pollution affects the rainforests, check out the Environmental Pollution and Tropical Rainforests article.

And … the effects of rainforest destruction?

Rainforests provide a number of very important ecological services, and rainforest destruction leads to their disruption.

First and foremost, rainforest destruction causes the loss of plant and animal diversity and disruption in global climate patterns, alongside many other side effects such as floods and droughts, to name just a few.

The loss of animal diversity also means that rainforest destruction is a major cause of animal extinction and endangerment.

And the effects of deforestation may be truly unpredictable. For example, in March 2008 it was reported that rainforest snakes, such as the anaconda, invaded a city of Belem in Brazil because deforestation was destroying their natural forest habitat.

It is unfortunate that developing countries, especially African ones, are most affected by the negative effects of rainforest destruction – as if these countries don’t already have enough to deal with.

It will certainly take a lot of concerted action by all the countries and governments to make sure we, the humanity, are not too late to halt this destructive process.

Written by: Irina Bright

Original publication date: 2008

Updates: 2016

Republication date: 2020

References

1. Leigh, E. G. (1999). Tropical Forest Ecology: A View from Barro Colorado Island. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 233 . Retrieved November 15, 2007 from Questia.com

2. Forest. (2004). In The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. Retrieved November 15, 2007 from Questia.com

3. Status of the World's Tropical Forests. (2007). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 16, 2007 from Encyclopedia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9118267

4. Williams, M. (2001, July). The History of Deforestation. History Today, Vol. 51. Retrieved November 15, 2007 from Questia.com

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005. Retrieved November 14, 2007 from http://www.fao.org/forestry/site/32038/en

11. Mygatt, E. (April 4, 2006). World’s Forests Continue to Shrink. Earth Policy Institute. Retrieved November 15, 2007 from http://www.earth-policy.org/Indicators/Forest/2006.htm

12. Amazon Rainforest. (November 5, 2007). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Amazon_Rainforest&oldid=169357560

13. Mygatt, E. (April 4, 2006). World’s Forests Continue to Shrink. Earth Policy Institute. Retrieved November 15, 2007 from http://www.earth-policy.org/Indicators/Forest/2006.htm

14. Park, C. C. (1992). Tropical Rainforests. New York: Routledge, p. 67. Retrieved November 15, 2007 from Questia.com

15. Ibid., pp. 67 – 68

16. Illegal logging. (November 15, 2007). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 16, 2007 from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Illegal_logging&oldid=171763873